The Importance of Payrolls

As the gold standard of economic reports, payrolls carry significant weight. Given their influence on Treasury yields, they indirectly have the power to move the prices of all financial assets. Moreover, payroll data impacts key decision-making bodies: the Fed, Congress (if you believe them—I don’t), and Wall Street strategists and analysts.

Bottom line: payrolls move minds and money like no other report. That warrants attention.

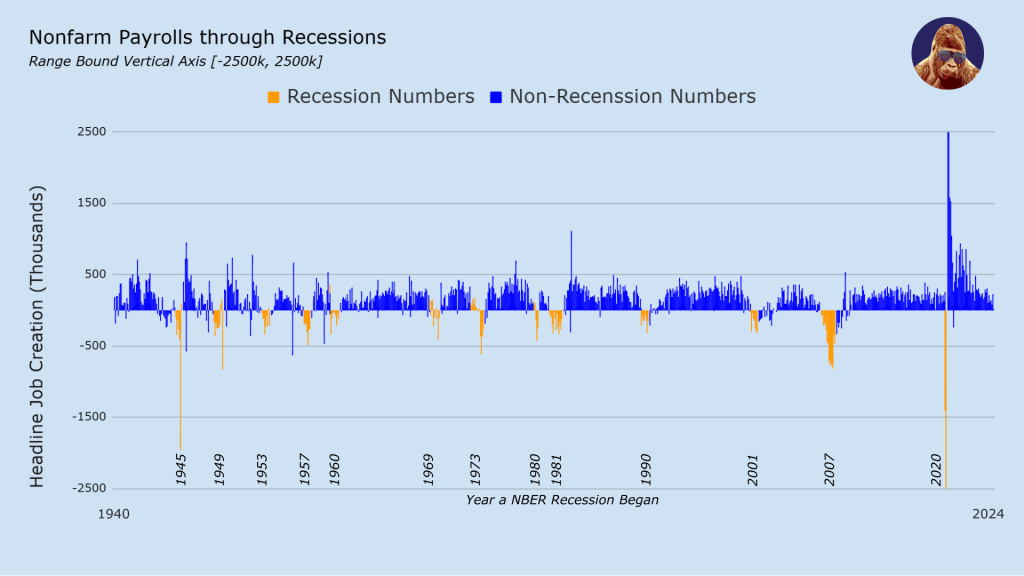

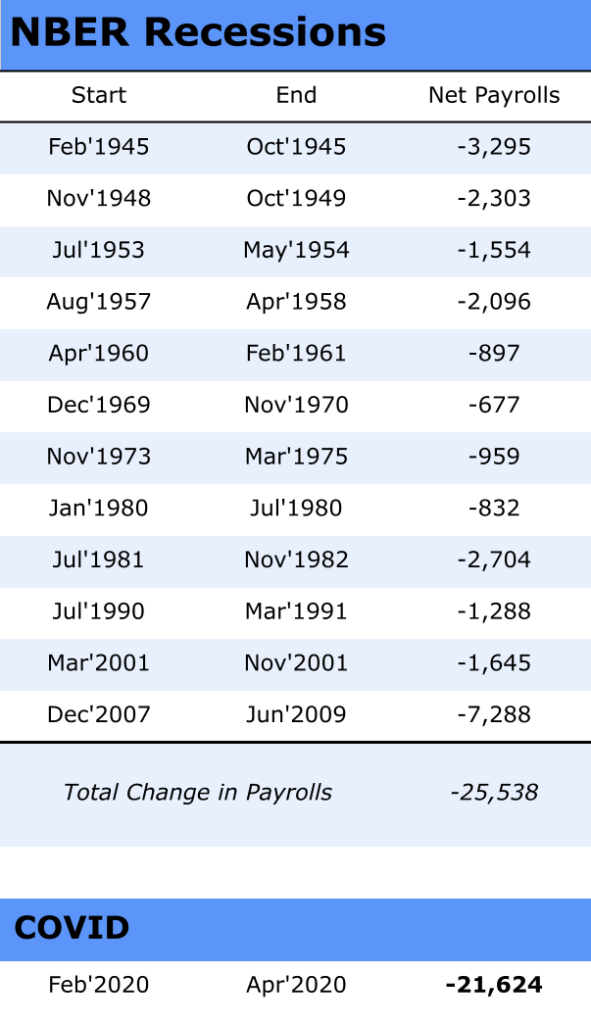

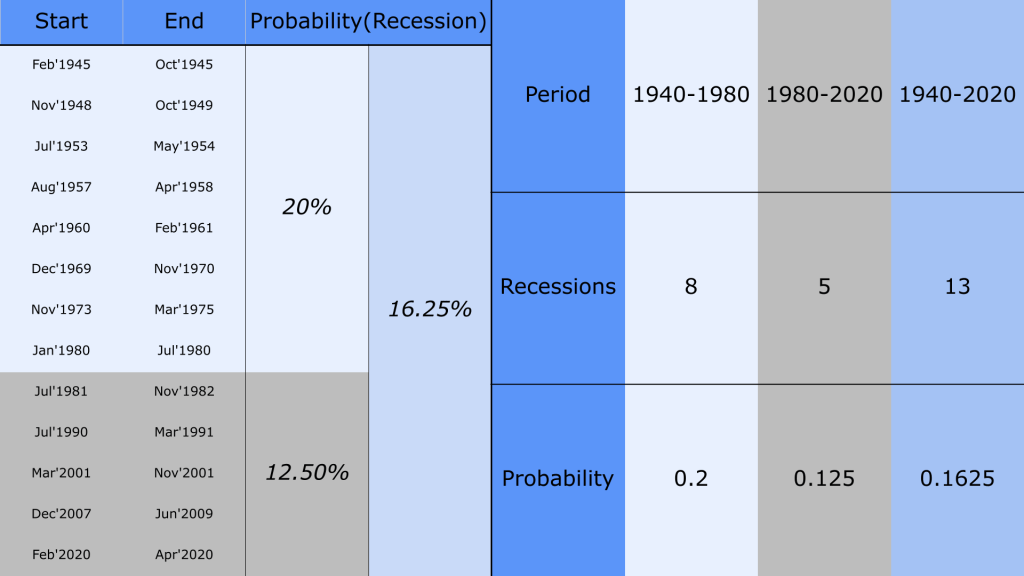

Before continuing, some context: I deferred to the NBER for recession periods. The 13 periods highlighted may not include all bear markets, consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth, or other commonly used rules of thumb. For the purposes of this exercise, the NBER is the arbiter of recessions, plain and simple. By the nature of their process, the NBER makes the call only after the recession has already begun.

Now, let’s dive right in.

What A Recession Looks Like: Lots of Job Losses

Below is a bar chart showing all 1-month changes in payrolls—job creation—from 1940 through today. Months shaded in orange represent periods the NBER characterized as a recession; the blue represents all other months.

While it isn’t uncommon for NBER to pinpoint the start of a recession before the first negative payrolls number appears, there has never been an NBER recession without consecutive months of job losses. Due to its extremely short duration, COVID may appear an outlier. However, the total payroll losses during the COVID recession were nearly as severe as those of all other recessions since 1945 combined: 21,624 jobs lost during COVID versus 25,538 across all other recessions. For reference, the median payroll contraction during an NBER recession is 1,645.

We Are Here

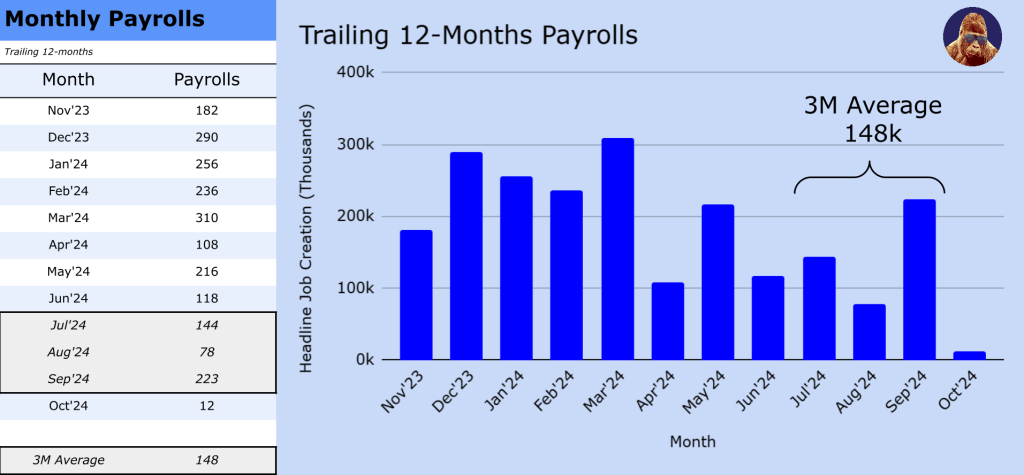

Compared to the rest of the dataset, the last twelve months look nothing like a recession. In fact, payrolls haven’t turned negative since the outlier COVID-recession was offset by an equally anomalous V-shaped recovery. As shown, October came close (12k preliminary), but for now, we can reasonably attribute this to distortions caused by Hurricanes Helene and Milton.

If the upcoming jobs report rebounds toward the 3-month average (excluding October) of 148k, we can conclude October was more about the hurricanes and less about the economy. It’s also possible that October’s number will be revised upward. However, if job creation doesn’t bounce back, we should brace for volatility in both bond and stock markets, along with a more serious discussion about the economy’s trajectory.

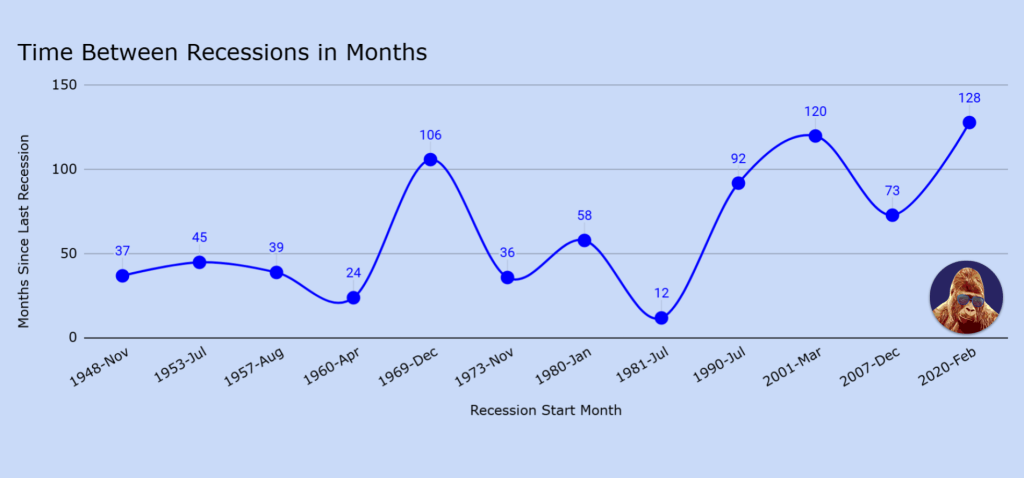

An Observation: The Time Between Recessions Appears to Be Increasing.

This hypothesis doesn’t perfectly correlate with the data, but it seems more plausible than the alternatives – namely, the time between recessions decreasing or remaining stagnant.

When I look at the chart, it seems that the longer the economy goes without a recession, the less likely one becomes in the immediate future. From my perspective, if the economy can avoid a double-dip recession – falling back into one immediately after getting out – it’s likely to hold steady until the next unexpected event.

Another way to frame this is by splitting the 80-year period from 1940 to 2020 into two equal segments. First, let’s establish a baseline: over the entire period, the U.S. averaged 0.1625 recessions per year (13 recessions divided by 80 years), implying a 16.25% chance of recession in any given year. Between 1940 and 1980, the implied probability was 20%. Between 1981 and 2020, it dropped to 12.5%.

Net-net, the data seems to suggest that recessions are happening less frequently. This brings me to my next point.

The Wrong Way To Look At It

I want to address a certain demographic that feels we’ve had it “too good” for “too long” or believes that the wealth creation through the stock market has become “too easy to be trusted”. I feel this mindset has to be rooted in the “Protestant work ethic” or some other phenomenon I read about in high school. This cohort would likely argue that a recession is overdue and, as a consequence, that years of stock market gains are destined to evaporate when we’re no longer “lucky enough” to avoid a recession.

What They’re Missing

What this group views as luck, I view as learning.

Just like anything else, the more time you invest in something, the better you get at it. The stock market is driven by earnings delivered by companies, and I believe today’s companies have learned from those of the past. As a result, they are better at making money and protecting margins, leaving modern economies less vulnerable to commodity shocks and less cyclical in nature. Perhaps, this is what that particular cohort fails to see.

Thanks to technological advancements over the last 20 years, even massive companies can now move quickly in response to emerging threats. From my perspective, a recession will need to be triggered by an unpredictable or extremely fast-moving catalyst – something no one has time to prepare for.

While I can’t back this up with data, I believe the world’s fixation on inflation and recession, combined with the long lead time the Fed provided prior to tightening, allowed key players to prepare. As a result, the recession that has been widely predicted since 2021 has yet to materialize (knock on wood). I think one of the biggest lessons from the last three years is that when leaders are aware of potential threats, meaningful action can be taken to mitigate them. I don’t believe this same level of outcome-altering preparation was possible in prior periods. Today’s strongest economies and companies – built on lessons from the past and bolstered by superior technology – leave us with greater control over our economic destiny.

How I View It

To conclude, I don’t subscribe to the idea that the time since the last recession has predictive value for when the next one will occur. Sure, we’re one day closer to the next recession tomorrow than we are today, but beyond that, I don’t think it adds much value. This kind of thinking assumes that the time elapsed since the last recession is an input variable – an x-variable – in a formula for the next. I just don’t see the logic in that.

Instead, I think we should explore why the intervals between recessions appear to be increasing and treat this as an output variable – the y-variable. Let’s focus on identifying the inputs that have created this desirable outcome: longer gaps between recessions. From there, we can determine which practices are sustainable and prioritize accordingly.

Leave a Reply